09 Sep Is Low Traffic Neighbourhood (LTN) Greenwashing? Facts

According to data from the Office of Health Improvement and Disparities, air pollution stands as the most significant public health in the UK, resulting in an estimated annual toll of 28,000 to 36,000 deaths. Furthermore, the projected cost to the NHS and social care system between 2017 and 2025 related to air pollutants, specifically fine particulate matter and nitrogen dioxide, amounts to £1.6 billion. This alarming impact underscores the urgency of addressing the issue of air pollution, particularly in congested cities, where it poses a considerable threat to public well-being and contributes to premature deaths.

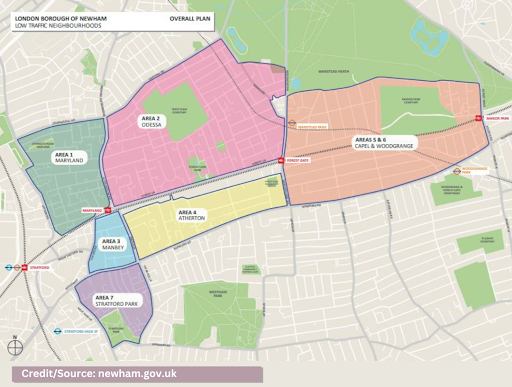

In response to this critical concern, Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs), also known as Low Traffic Areas (LTAs) or Healthy Streets schemes, have been implemented as localised initiatives by the government. The core objective of LTNs is to tackle pressing environmental and public health challenges by curbing motorised traffic in specific residential areas within cities or towns. By doing so, LTNs aim to reduce traffic congestion, improve air quality, promote active transportation, and create safer spaces for pedestrians and cyclists.

However, the initiative is not rid of controversies, with critics accusing the government of greenwashing. This article explores evidence with regard to the effectiveness of LTNs in achieving their environmental goals. Evaluating the impact of LTNs on air pollution, road fatalities, and physical inactivity will shed light on their role in addressing public health issues associated with widespread car use.

Why LTNs?

LTNs were introduced by the government to curb traffic in residential areas through a variety of measures. The goal is to decrease the number of vehicles on the roads, encourage more people to walk or cycle, and reduce crime rates. One of the key aims is to combat CO2 emissions in areas where LTNs are implemented. The idea is that by restricting “rat-running” – the use of residential roads as shortcuts by drivers – residents can access roads more efficiently, and emergency services can navigate major cities with greater ease. LTNs utilise barriers, bollards, road signs, planters, and, in some cases, automatic number plate recognition cameras to restrict motor vehicle access while allowing pedestrians and cyclists through.

In 2022, it is reported that nearly 7.5 million penalty notices were given to motorists in London, which can largely be attributed to the introduction of novel Low Traffic Neighbourhoods and revised school street regulations. Data reveals that the collective count of fines, with potential fees of up to £160, escalated by 2.2 million in comparison to the previous year, marking a substantial 41% surge to reach 7,472,886. While LTNs have seen increased attention and funding in recent times, some critics argue that they may not be as effective as portrayed.

Criticism

Greenwashing is a deceptive marketing tactic that misrepresents the environmental responsibility and sustainability of a product, service, or initiative. By exaggerating environmental benefits, it aims to attract environmentally conscious consumers.

The critical question surrounding LTNs is whether they represent a sincere step towards greener and healthier cities or whether they merely serve as superficial measures, creating the illusion of sustainability without achieving substantial change.

Key criticisms include;

- Traffic Diversion: The major challenges arise from redirecting drivers to alternate routes, leading to increased travel time due to the presence of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs). In fact, the fact that traffic volumes on minor roads have flatlined in London since 2009 have motivated many to posit that Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) aren’t needed. Also, this extended travel duration results in heightened emissions from vehicles. While there are assertions that LTNs could enhance access to emergency services, certain LTNs are designed to prevent vehicles larger than bicycles from passing through. Consequently, larger vehicles face a situation where they cannot reach their destinations more efficiently than they could before the introduction of LTNs.

Another criticism associated with Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) is the labelling of these initiatives as “roadblocks.” However, this term is not accurate, especially given that pedestrians and cyclists maintain the same access as before. Even for motor vehicles, there is no complete closure of routes. The restriction only affects traffic, which aims to prevent residential roads from being used as shortcuts. While it’s true that certain short car trips might take longer, this inconvenience aligns with the objective of encouraging individuals to explore alternative modes of transportation.

- Democratic Considerations: Some critics argue that LTNs lack democratic consultation, particularly in cases where they were swiftly implemented during the initial response to the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside other temporary measures like expanded bike lanes and wider sidewalks. This situation has prompted concerns about transparency and public involvement.

Potential Benefits of LTNs

The primary advantage of Low Traffic Neighbourhoods (LTNs) lies in their ability to mitigate air and noise pollution by curbing through traffic. LTNs also contribute to a reduction in carbon emissions, primarily due to reduced vehicle traffic. With fewer cars on the road, the air quality improves, and greenhouse gas emissions decrease. But, this benefit extends beyond a cleaner and quieter urban environment and also promotes active transportation modes such as walking and cycling. Statistical data reveal that the implementation of low-traffic neighbourhoods resulted in an overall 10% reduction in total street crime, with this effect becoming more significant over time, reaching an 18% decrease after three years. Notably, more severe categories of crime, such as violence and sexual offences, experienced even larger reductions. However, bicycle theft increased, likely due to higher cycling rates. While the veracity of this data has been a point of contention, proponents of LTNs argue that these initiatives facilitate improved access for emergency service vehicles, enabling quicker response times.

The perspective of residents residing within LTN zones is predominantly positive, with many expressing appreciation for the positive transformations within their neighbourhoods. Notably, these improvements have garnered praise for enhancing the overall quality of life in these areas. Supporters of LTNs also assert that these initiatives foster heightened social interactions among neighbours, thereby bolstering the sense of community and neighbourhood cohesion. An additional positive outcome arises from the increased prevalence of walking, which benefits local businesses. This shift leads to more foot traffic passing by these establishments, augmenting their customer base and generating economic opportunities as pedestrians replace motorised transportation.

In conclusion, LTNs deliver a multitude of benefits beyond pollution reduction, including the promotion of active lifestyles, improved community ties, and economic gains for local businesses. While there might be controversies surrounding certain aspects of their impact, the positive feedback from residents and the potential for more sustainable and vibrant neighbourhoods underscore the potential of LTNs to be effective and transformative urban interventions.

No Comments